|

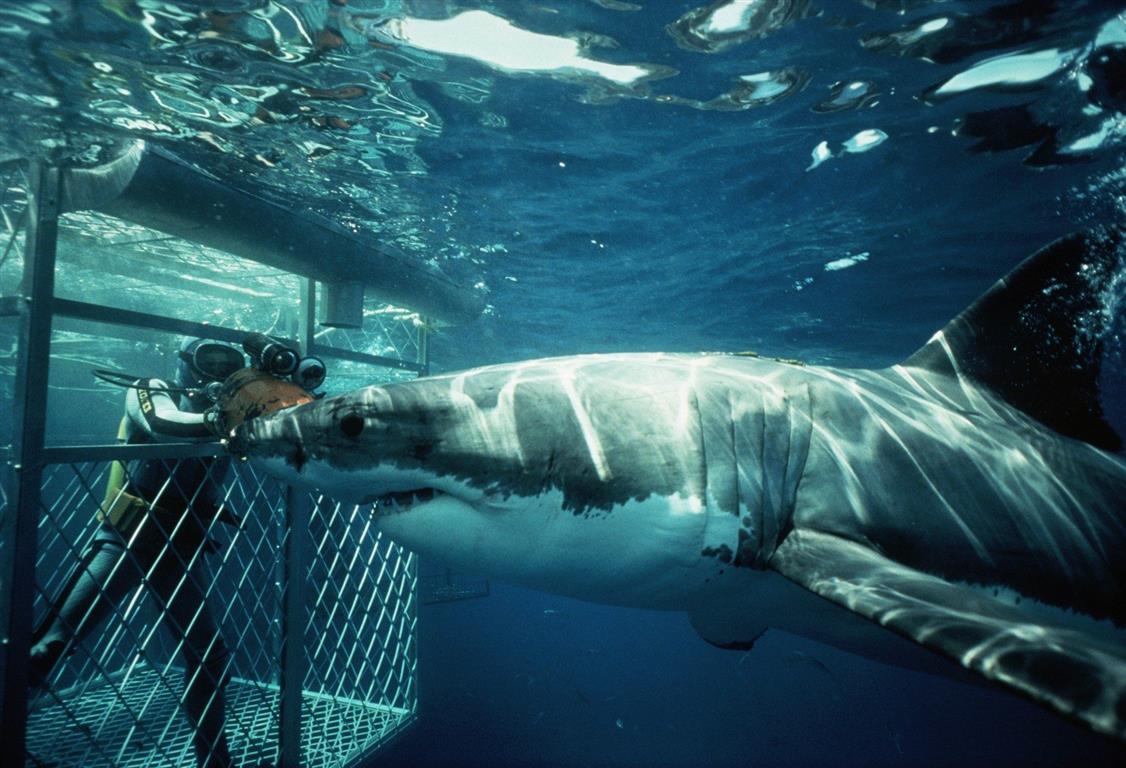

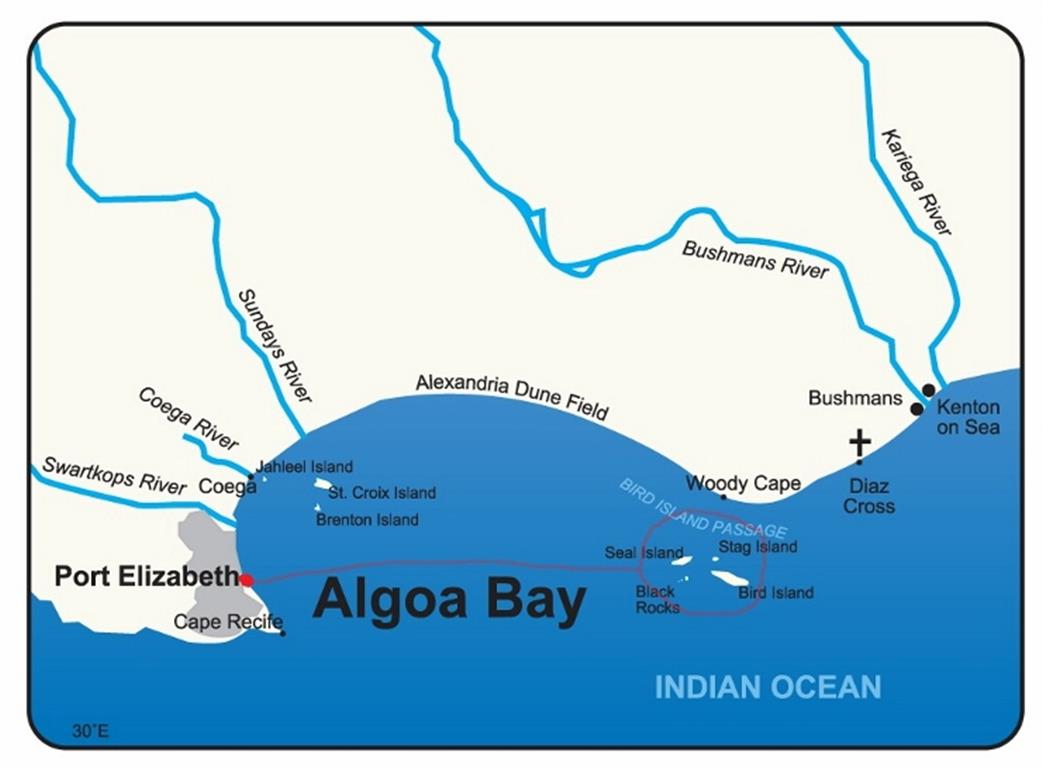

I surf. Often alone. Often at sunrise & sunset. I pee in my wetsuit. I’m scared of sharks. They’re big, and have more teeth than I do. And just like you, I don’t want to be on the lunch menu. Carcharodon carcharias aka the Great White Shark, from the Greek ‘karcharos’ meaning sharp and ‘odous’ meaning teeth. It’s the world’s ultimate ambush predator that’s been around for 400 million years. A 7m long, 2 ton, 3000 toothed ocean-dwelling mugger who doesn’t blink. It lives where we play. And that makes us nervous…. Even more so when you open the mornings newspaper to discover that shark cage diving is about to start in Algoa Bay. The DEA has just awarded a license to Raggy Charters to operate a shark cage diving operation at Bird Island, near Woody Cape. Now it's hard to be objective about shark cage diving. It's a massively emotive subject. And most peoples knee jerk reaction is that it is a super kak idea. Let's look at the facts. One of my favourite words is Perception. "[per-sep-shuhn] Noun. The way in which something is regarded, understood, or interpreted." It’s what can make us see black and white when in reality all there is are shades of grey. It can also make us see grey, when things are black and white. We all think that the number of attacks from big whites is on the up, and there are far more sightings. Conversations in the line-up and the car park frequently turn to what’s behind the recent increase in activity - "It must be all the shark cage diving" they say. We’re wired to see something rather than nothing, to seek out patterns rather than accept randomness. Everyone seems to have a shark story or have heard a shark story. Then there’re these ou’s that are dumping blood and guts over the sides of their boats to make a buck. At our expense!? The neutral observer may see our concern as ironic given that the ocean is the sharks playground not ours; to them, I say stay on the beach. We aren’t neutral. We’re in that ocean playground daily, and we don’t want to be the next statistic. Don’t get between us and our surf. It’s not called an addiction for nothing. Despite the fact that the statistics show that there isn't a trend of increasing attacks evident over the last 22 years, the presence of white sharks particularly in the False Bay region, and stretches along the coast such as Plett, do seem to have become increasingly conspicuous. Because we’re surfers we don’t care that we have more chance of getting hit by lightning or killed by a falling coconut than being bitten by a Great White. Who gives a damn about coconuts when you’re sitting on your board getting lazily circled by something larger than you with considerably more teeth. Even if he doesn’t bite us, we’d honestly prefer not to see him. Even if the records show there’s only an average of 3 Great White attacks per year along our coastline, and of those only 40% are on surfers, the fact is that none of us want to be one those unlucky three. Just because the stats from the last 22 years don’t seem to show an increase in great white attacks, that doesn’t mean that can’t change in the future. If there’s one thing that science teaches us is that nothing is absolute, and that what’s accepted as correct today might not be so tomorrow. After all, no-one believed Galileo at first when he said the Earth revolved around the sun. So damn right we want to know what influence cage diving and chumming has on the white’s behaviour. Because what might be happening now might end up influencing our predisposition to attack in the future. Sharks live upwards of 40 years, so what they’re learning now might get applied long into the future. Irrespective of whether there’s been an increase in great white shark attacks or not, investigating the effect of chumming on their behaviour remains a relevant argument. We don’t want to be caught standing impassively on the sidelines if there’s something that could be potentially increasing our risk of attack. Hey Chummy…. A heated debate rages over whether shark ecotourism (a dichotomy of terms if ever there was one) otherwise known as shark cage diving, may alter shark behaviour and in doing so increase the propensity for human/white shark encounters. Much of the debate centres on their use of chum as a means of attracting the sharks, with the argument being that this is conditioning sharks to associate us with food. It just seems to makes sense at first glance. Pavlov says ring the bell, feed the dog. Dog learns bell means food. Now he drools every time the bell rings. Shark diving boat dumps chum, shark goes to boat, eats bait. Shark learns boat means food. Yes, so far the science supports that. Shark learns boat means food and bites human? We’ll get back to that one later. (“Pavlovian Response - a learning process that occurs when two stimuli are repeatedly paired; a response that is at first elicited by the second stimulus is eventually elicited by the first stimulus alone.”) Both local and international studies have shown that chumming can result in a change in the white sharks behaviour. Local shark researchers Ryan Johnson and Alison Kock found that although most of the white sharks they monitored in False Bay and Gansbaai showed no evidence of conditioning to chumming, some did. As Matt Dicken, PE based marine biologist and shark researcher, explains “To evoke Pavlovian conditioning in Great Whites requires the equivalent of the ‘Perfect Storm’. You have to repeatedly feed the same shark every day for a prolonged period. There has to be that predictable reward. But the Whites are transient in nature, often staying in an area for just 1-2 weeks before moving off and returning at a later date. It’s not often we’ll see the same individual on a number of consecutive days when we’re out on the boat, so the opportunity to develop a Pavlovian response would be rare.” Matt goes on to point out that even if conditioning does occur, if the conditioned reflex is not maintained by regular positive reinforcement, it will eventually be lost altogether. The hiccup is that sharks are clever critters - they haven't been around for millions of years cos they're like doff sheep, and probably don't have to have a Pavlovian response drummed into them to quickly work out "here's a lekker spot to grab a chow". A recent Australian study in the Neptune Islands showed a more noticeable effect of chumming on white shark behaviour. An earlier study at the same location had shown a negligible effect of chumming, yet just 5 years later the changes were significant. Shark Cage diving had increased markedly in the interim, with dive days going from an average of 128 days/year to 278 days/year. The study found that sharks were resident for greater periods of time (11 days to 21 days), with a significant increase in the length of each visit (defined as the average number of consecutive days spent at in the area during residency periods) from 2 days to 6.5 days. The researchers point out that this doesn’t mean that the actual number of sharks had increased, but rather showed that they’re staying for longer periods and that each individual was seen more often. Daily shark movements changed to more closely match the arrival and departure of shark cage dive operators, with a peak in arrival times of sharks immediately prior to the arrival times of the boats. Disconcertingly this pattern was noted even on days when operators weren’t present. The observations of both the Australian & South African studies suggest that chumming can change the way sharks behave. However, there is no direct evidence as yet to suggest that these changes have been harmful to the sharks or whether they may lead to changes in their behavior at any other location. And their behavior towards us. So does shark cage diving increase our risk of attack? As Ryan Johnson points out in his study “Would a white shark conditioned to associate a 40ft chumming boat and cage have this conditioned reflex stimulated by the detection of a 6ft swimmer or board rider?” Pretty valid point that. He points to something called Rearrangement Gradients, which basically predicts that progressively larger deviations away from the conditioned stimuli, in this case the cage diving boat, would reduce the stimulation of the conditioned response, being attempted feeding. In other words, the conditioned 'feeding anticipation' response of the white shark would be less likely to be evoked by anything that didn’t closely resemble the cage diving boat. So the less it resembles the boat, the less likelihood of association. I don’t know about you, but I don’t think we look much like a boat? And we don’t smell much like a chumming boat either. It’s actually this sensory stimulus that entices the white shark to the cage diving boat to start with. Sharks smell better than they see. So they smell the chum first, and then head over to check out the boat. So what we have is a scenario whereby a similarity in both smell and appearance is required in order for a conditioned shark to associate a new object with a cage diving boat and have its anticipated feeding response evoked. I think it’s safe to conclude we don’t tick either box, and that we can discard the notion that there’s a direct causal relationship between chumming and human/shark encounters…….meaning it sees us and thinks “Food!” “We draw conclusions on the based on what we see. But it’s important for us to remember that just because there is a correlation between two facts, it doesn’t necessarily a cause/effect relationship between them.” But that doesn’t necessarily let cage diving off the hook. If it’s capable of keeping sharks in the area for longer periods, and this area happens to be within close proximity to where there’re surfers or other water users, then it’s not implausible to consider that our exposure to these sharks could increase, and with that the potential for an encounter. So an indirect relationship between cage diving and increasing human/shark encounters isn’t implausible. So it may be that the location of the cage diving operations is a key element to consider in this debate. Although chumming doesn’t draw more sharks into the area, it does create a focal point and makes them hang around for longer. If this “hanging around” area happens to include surf spots or bathing beaches within close proximity, would it not be reasonable to assume that ours paths might cross a little more often? Upsetting the balance Our safety aside, if chumming can cause behavioural change in sharks, this could cascade down the entire ecosystem by changing the shark’s interaction with other species, and have potentially detrimental consequences. Understanding the impacts of such changes is complex because each shark is only a transient resident to these locations, and only exposed to chumming whilst there. “I instinctively feel that chumming is wrong, especially from an environmental angle - enticing wild animals with blood for the pleasure of humans with cameras doesn't ring well with me.” Conn Bertish The challenge is to reduce the impact of shark cage diving on both sharks and the ecosystem whilst still maintaining a viable industry that contributes significantly to the local economy. The platform that ethical cage diving provides for Great White shark education, research and conservation should not be underestimated either. When money talks, do rules walk? The researchers noted that conditioning would only arise if “operators intentionally and willfully contravene current permit regulations prohibiting intentional feeding of sharks”. Which in a South African context is not an entirely unlikely situation. Particularly so when you there’s so much at stake. A local socio-economic study found that the 8 cage diving operators in Gansbaai generated an income of almost R30 million from direct ticket sales over a 12 month period. The likelihood of a R30 million industry self-regulating to the benefit of the environment not the balance sheet is well, unlikely. There’re tourists on board who’ve paid good money for their Discovery Channel experience. But nature isn’t DSTV on demand. Whites are elusive creatures, they don’t come when you whistle or click your fingers. Hence the need for chumming. It’s meant to be limited to 25 kg per day per operator, natural fish products only. But how do we know these rules are being observed? How do we know the sharks aren’t being fed? It’s certainly not to say that every cage dive operator is unscrupulous, far from it, but there might be those that are. Responsible cage diving – a dichotomy or a possibility? There’s too much money involved for the call for a ban on cage-diving to ever succeed. But it can be done in a more responsible manner; so what is the sustainable way forward? Concerned NGO's have called for the appointment of an independent ECO (Environmental Compliance Officer) for each boat, who will ensure that regulations are followed. Reducing the level of chumming, as well as the number of days per year its permissible may also assist in reducing the likelihood of conditioning responses. Less exposure to less stimulus less regularly means a lower chance of conditioning. There’s also anecdotal evidence of sharks being attracted by low frequency sound, so a non-chum alternative may be possible. As cage diving operations could be contributing to sharks remaining in an area for longer, location becomes a critical component. Restricting operations to locations in those areas that are not in close proximity to frequently used beaches should seriously be considered. As the crow flies (or the shark swims) Bird Island is just under 60km from PE's southern beaches. Peek-a-boo. Where-are-you? Understanding white shark demographics & distribution plays a key role in establishing our potential risk profile. If we know when and where they’re most likely to occur we have a better chance at minimising our chance of an encounter. That's why the municipality should renew funding for BayWorld's White Shark study - so Matt Dicken can continue his important research in Algoa Bay. White sharks aren’t home bodies, they’re travellers. Swimming the oceanic equivalent of the N2 from Cape Town up to Richard’s Bay and beyond. Some even make the transcontinental journey to Australia and back. There seem to be key places where they spend most of their time, and then move rapidly between these areas once they decide to change location. It’s surmised that these hotspots are related to feeding, resting, mating and socialising. One of the key hotposts for Great Whites are seal colonies. Seal, Dyer and Bird Islands, and Robberg peninsula, are the McDonald Drive-throughs of the oceanic Highway. Seal-burgers are top of the menu. Bigger seal colonies generally mean an up-size in the shark population within the vicinity. It’s not a coincidence that many of the white shark attacks happen within the general area of seal colonies. More sharks in an area means the higher our chances of bumping into one. So are we on the menu? No. Luckily for us great whites think we taste kak. The high-caloric, energy-rich blubber of seal pups gives them far more bang for their buck. We didn’t evolve alongside the shark as ocean dwellers, so we don’t slot into their natural food chain at all. If they did want to eat us there’d be a lot more than 63 human/white shark encounters over 2 decades, so it’s safe to say they definitely don’t hunt us as natural prey. So why do we get bitten then? Turns out sharks are exceedingly curious, but in the absence of hands to pick something up and give it the once over, they rely on their mouths instead. This might explain why over 70% of great white bites on humans are a bite and release only. Much of the time the shark just wants to see what we are, and then on discovering that we don’t taste particularly nice, proceeds to spit us out and move on. Unfortunately our design is such that we have numerous large arteries close to the surface that don’t respond well having 3 rows of razor sharp teeth embedded into them. That’s not to say that there aren’t instances where the victims get eaten, but these are the exception rather than the rule. A recent shark incident at Seals saw Ross Spowart get a bite on his knee But there do seem to be more whites and more incidents!? Even thought the stats don't clearly point to an increase in attacks, there do seem to be more whites about. And no-one really knows why. There’s a myriad of theories as to what might be responsible. Everything from climate change, to estuary outflows, more sharks or more seals, a change in distribution patterns within the areas themselves, shark cage diving, chumming, more people in the water over longer periods; the list goes on. Most likely it’s a combination of a variety of factors, some we may not even yet have considered. “We have a deep need to make up a narrative that serves to make sense of a series of connected or disconnected facts. Our correlation calculators pull together these cause and effect stories to help us understand the world around us even if chance has dictated our circumstances. We fit these stories around the observable facts and sometimes render the facts to make them fit the story.” Psychologist Gerald Guild. We need something tangible to direct our emotions towards when we’re dealing with our primordial fear of shark attack, and it’s far easier to direct our ire towards something visceral like shark cage diving rather than an abstract construct such an increase in the number of water users. The explosion of social media and our heightened interconnectedness means news of a shark sighting can extend far beyond our immediate circle of friends as was the case until the advent of Facebook, to now reaching a diverse and dispersed audience within minutes. The last word

Sharks are integral cogs in our marine ecosystem and certainly deserve our respect and protection. Pull them out of the marine equation and it could collapse like the proverbial pack of cards, with consequences far beyond what we can comprehend. But at the same time it doesn’t mean we have to like them, or be happy about the fact that we seem to be seeing more of them in close proximity to where we swim or surf. Modern marine coastal management stresses an ecosystem based approach. It’s not us or them, it’s us and them. We just have to work out how to keep the balance right for both parties. Happy sharks. Happy humans. Wouldn’t that be a happy ending? Where does shark cage diving fit in to all of this? Time will tell. Shark attacks may be rare. But then rare things happen all the time. Someone does win the lottery, people do have meteorites land in their lounge, people are struck by lightning twice. Personally, I’d rather win the lotto. (This blog post contains extracts from a feature on Great White Sharks I wrote for Bomb Surf magazine a while ago, for which I did a heap of research)

Bruce

5/11/2018 12:47:22 am

Excellent article thank you.

Dr Peter A.Schwartz

5/16/2018 10:18:06 pm

Interesting article. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorMillerslocal Archives

July 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed